Change Your Chronotype to Change Your Life

Reset Your Internal Clock in 3 Weeks to Boost Mental and Physical Health & Performance

I've often heard people say, “I’m just not a morning person.” For much of my life, that was my reality too—late-night study sessions, evenings out with friends, struggling to fall asleep before midnight, and groggy awakenings were the hallmarks of my night-owl existence. Inspired by high performers like David Goggins, I decided to experiment with early rising. Transitioning to a morning routine was challenging—especially when all my friends were dedicated night owls—but shifting my schedule to get my workouts in early and start my day sooner transformed my mood, enhanced my performance, and completely reshaped my life.

Evidence shows that you can reset your internal clock through deliberate, non-pharmacological interventions in a matter of weeks. By gradually shifting your sleep schedule earlier, this can lead to significant improvements in mood, stress, and even physical and cognitive performance. In other words, being a night owl isn’t a life sentence—there are proven strategies to help you become more of a morning person.

In this post, I’ll share the science on how shifting your chronotype can change your life, explore the underlying biological mechanisms, and provide practical protocols you can start implementing today.

Why “Night Owls” Struggle

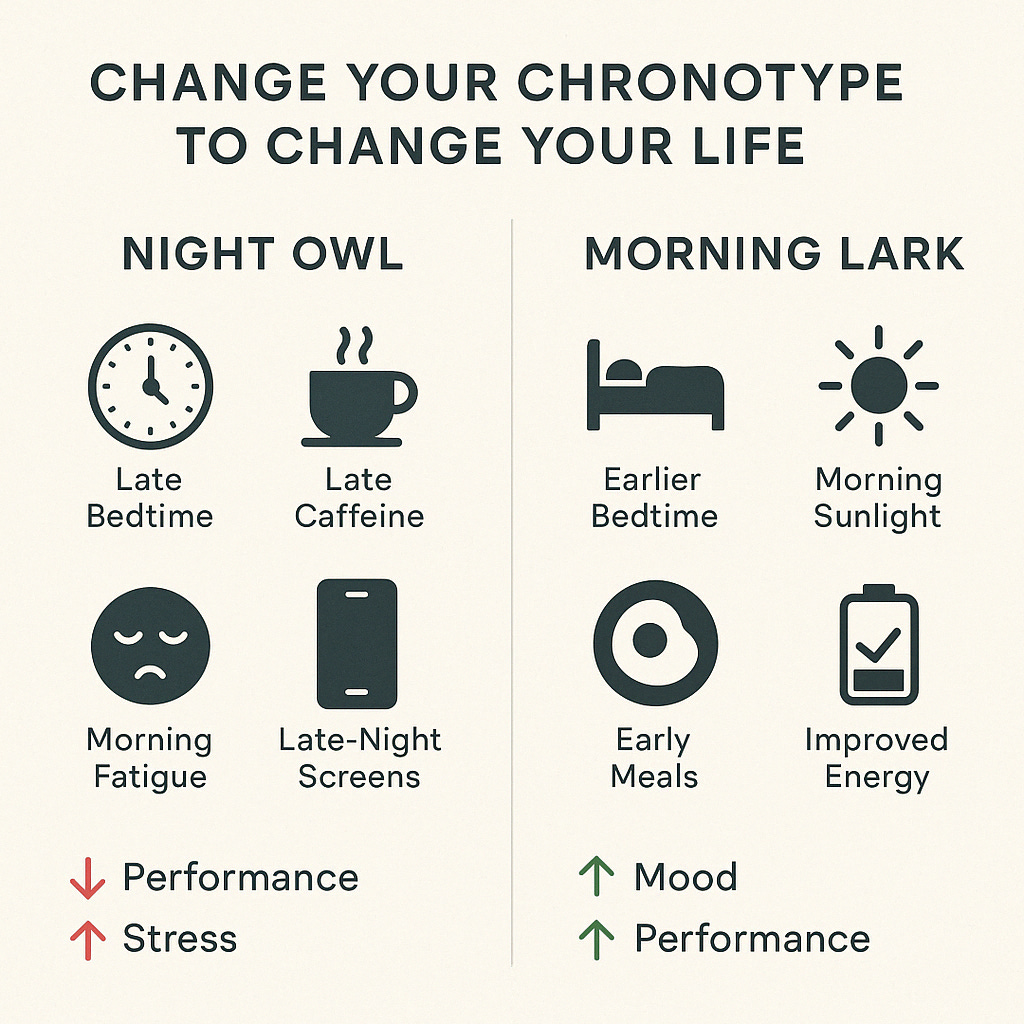

A “night owl” (also known as a late chronotype) is someone whose internal clock runs late, leading to:

Delayed sleep onset (often after midnight)

Late wake-up times (sometimes late morning or even past noon)

Difficulty fitting into a 9-to-5 schedule without chronic sleep debt

Over time, this mismatch between internal rhythm and external demands can lead to:

Researchers have found that individuals with misaligned or “delayed” sleep-wake cycles often show disrupted melatonin release and higher evening cortisol levels, both of which can make it harder to wind down at night. Chronic misalignment is also tied to increased inflammation and mood disturbances. In short: if you’re a night owl forced into an early-bird world, you may be running on partial jet lag most days.

So how can we help night owls align better with typical working hours—or, at least, shift closer to them? That’s precisely what researchers tested.

A Key Study

In a study published in Sleep Medicine, researchers enrolled healthy young adults identified as “night owls” using questionnaire data. Each participant’s sleep-wake schedule and internal circadian markers were measured with:

Actigraphy (a watch-like device that records movement to infer sleep timing)

Salivary melatonin (dim light melatonin onset, DLMO)

Cortisol awakening response

Participants were then randomized into two groups: one that followed a specific “chronotype-shifting” intervention and a control group that stuck to their usual habits.

What They Did

Those in the experimental (intervention) group received a detailed schedule to follow for three weeks:

Move bedtime and wake-up time about 2–3 hours earlier than usual.

Wake up at the same time every day.

Maximize morning light exposure (e.g., open the curtains, go for a walk outdoors).

Reduce evening light exposure (e.g., avoid bright room lights and electronic screens close to bedtime).

Have meals at set times—particularly eating breakfast right after waking and avoiding late dinners (after 19:00).

Avoid caffeine after 15:00.

Schedule exercise in the morning if already part of your routine.

Avoid naps in the late afternoon or evening.

By contrast, the control group received only one general instruction: eat lunch at the same time every day (which was not expected to shift sleep timing in any significant way).

Key Findings

After three weeks, the results were striking. Compared to pre-intervention:

Sleep & Circadian Phase

Sleep onset was about 1.7 hours earlier in the intervention group.

Wake-up time advanced by roughly 1.9 hours, with no loss in total sleep duration or efficiency.

Melatonin onset (DLMO) shifted earlier by nearly 2 hours.

Peak cortisol awakening time advanced by about 2.2 hours.

In other words, it was a true shift in internal circadian timing, not just a forced earlier bedtime.

Mental Health

Self-reported depression and stress scores significantly decreased.

Anxiety didn’t change as much, suggesting depression and stress might be especially tied to late chronotype misalignment.

Performance

Daytime sleepiness went down notably in the morning (08:00) and early afternoon (14:00).

Cognitive performance (reaction time on a 2-min Psychomotor Vigilance Task) improved at 08:00.

Physical performance (max grip strength) also improved at 08:00 and 14:00.

Meanwhile, the control group—which did not adopt the earlier schedule—showed no improvements. In fact, many of their metrics trended toward a further delay in sleep timing, possibly reflecting a drift to an even more “night owl” lifestyle over those same few weeks

.

The Mechanisms

1. Entrainment by Light

The strongest “zeitgeber” (time-giver) for our internal clock is light exposure. Morning light advances your circadian phase, while bright light (e.g., blue light from devices) in the evening delays it. By waking up earlier and exposing yourself to natural light soon after rising, you’re nudging your clock forward each day.

2. Meal Timing

Eating late in the day disrupts the circadian clock because food intake acts as a powerful timing cue (zeitgeber) for peripheral clocks in organs like the liver, pancreas, and gut. When we eat late we send conflicting signals to the body: the central clock (in the brain) is preparing for rest, while peripheral clocks are being stimulated by food to stay active. This misalignment delays circadian rhythms, such as melatonin onset, and can shift the internal clock later, making it harder to fall asleep and wake up at consistent times. In contrast, eating earlier in the day reinforces the synchronization between the brain’s master clock and peripheral metabolic clocks. It helps phase advance the circadian system—promoting earlier melatonin secretion, improved sleep timing, and better alignment between metabolism and the sleep-wake cycle.

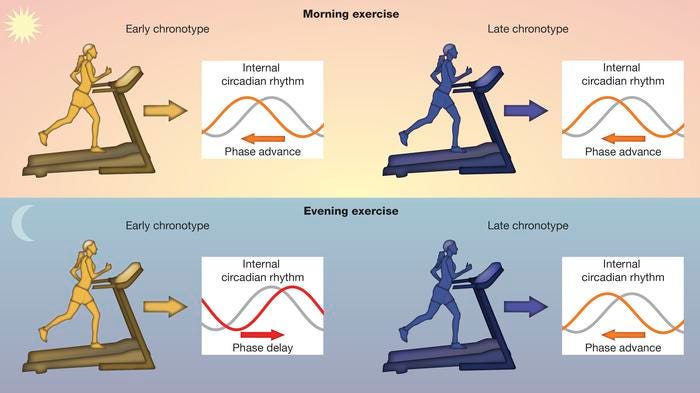

3. Caffeine & Exercise Timing

Both caffeine and exercise can shift circadian timing, though not as strongly as light. By pushing them to the morning or early afternoon, you remove signals that might otherwise reinforce a late rhythm. Morning exercise also boosts daytime serotonin, which is beneficial for mood, and helps you wind down more naturally at night. In some cases, evening exercise might actually shift the clock earlier in those with a late chronotype, but not as strongly as morning exercise.

4. Better Mood & Stress Handling

Studies consistently link sleep/circadian misalignment with heightened cortisol and inflammation, potentially explaining the link to mood issues like depression and anxiety. Shifting your clock earlier (so that your sleeping window actually syncs up with most daytime obligations) reduces social jet lag and allows you to perform better during the day, possibly contributing to lower stress and depressive symptoms.

Putting It Into Practice: A Protocol to Try

Below is a simplified, evidence-based protocol. Tailor it to your schedule and preferences, but aim for at least two to four weeks of consistency to see results:

Wake Up 1–2 Hours Earlier (Gradually)

Set your alarm 15–30 minutes earlier every day or two until you hit your target wake time.

Right after you wake, get into bright light—ideally by going outside. Even on cloudy days, natural outdoor light is far brighter than indoor lighting. If not possible or if you are waking before sunrise, try using a 10 000 lux depression lamp (I have two of them on my desk because I usually wake up 1-2 hours before sunrise).

Dim overhead lighting after dinner.

Use night-mode or blue-light filters on devices.

Ideally, avoid all screens two hours before bed. Blue wavelengths of light strongly suppress melatonin and interfere with sleep.

Protect Your New Bedtime

If you’re waking up earlier, go to bed 1–2 hours earlier as well.

Gradual is key: if you’re used to 2 a.m., aim for 1 a.m., then work toward 11 p.m. or even 10 p.m.

Warm showers 1-2 hours before bed can help get you into a state of relaxation and improve sleep.

Eat Breakfast Soon After Waking

Eating within ~30 minutes of waking can signal an earlier “daytime phase” to your body.

Avoid late dinners or late-night snacks (aim to finish eating for the day 2-3 hours before bed).

Or even earlier, if you’re sensitive. Caffeine can shift your clock later by delaying melatonin release.

If you already work out, schedule it in the morning or early afternoon if possible.

This helps reinforce a daytime signal for activity and can improve sleep quality at night.

Limit Evening Naps

If you must nap, keep it brief (15–20 min) and finish before 14:00.

Evening naps can push your bedtime back and make it harder to fall asleep.

Troubleshooting & Tips

Don’t Lose Sleep

The point is to shift, not shorten, your sleep. If you’re waking earlier, move your bedtime accordingly so you’re still getting 7–8 hours.Expect Some Initial Resistance

You may feel extra groggy at first—this is normal. Your clock takes time to adapt.Weekends Count

Avoid major “social jet lag” on weekends, or it could make it harder to progress. Keep your sleep/wake times reasonably consistent (within 15-30 minutes).Customize to Your Goals

You don’t need to become a 5 a.m. riser if that’s not realistic. Even a 60–90-minute shift can reap benefits.

Key Takeaways

Non-Pharmacological Intervention Works

Strategically shifting light exposure, sleep times, and meal timing has been demonstrated to advance the body’s internal clock by ~2 hours in just 3 weeks.Improved Mood & Stress

Participants in the study reported significantly lower depression and stress after moving to an earlier schedule.Better Morning Performance

Reaction time and grip strength improved during the morning hours that were previously “non-optimal” for night owls.Practicality is Key

You don’t need fancy labs—this was a real-world trial with everyday interventions like adjusting wake-up times and meal schedules.It’s Worth the Effort

If you’re a night owl struggling with morning lethargy, mental health challenges, or poor daytime performance, shifting your chronotype might be the game-changer you didn’t know you needed.

Final Thoughts

Evidence shows that we perform best when we align our schedules with our natural design as morning risers. While modern society often forces us into night-owl habits, shifting toward an earlier routine can lead to numerous benefits. By tapping into our innate chronotype, we unlock better mental and physical performance—proving that becoming a morning person isn’t just about waking up early, but about optimizing our lives for success.

Take it from someone who lived in the deep end of night-owl territory: small daily changes can produce surprisingly big payoffs—better mood, better focus, better performance, and greater resilience to stress. Give it a try, and see how resetting your clock just might reset your life.

Thanks for reading and joining me on this deep dive into sleep, chronotypes, and performance. If you found this helpful, consider subscribing—I’ll be covering a range of evidence-based strategies to optimize health, mood, focus, and energy.